The Sekida mountain range, running along the prefectural boundary line between Nagano and Niigata Prefectures, is a gently-sloping range parallel to the Chikuma River and JR Iiyama Line. In winter, seasonal winds from the Sea of Japan run up against the mountain range, creating ascending air currents. This unique geography makes Iiyama city, nestled at the foot of the mountain, one of the snowiest areas in Japan. Mt. Nabekura is the highest peak in the Sekida mountain range, and so covered in beech trees that they seem to form the mountain itself. Since ancient times, local people have used the beech forests for firewood collection and burning charcoal, creating a strong link between the mountain and their daily lives.

Beech trees are said to hold so much moisture that you can press an ear against the trunk and hear running water. These trees preserve nutrient-rich water, irrigating local towns' vast rice fields. According to local legend, "A tan (Approx.1,000㎡) of rice fields are watered by one beech."

Moreover, every house in this snowy region has a pond to thaw snow (called a yukidane), which makes use of water flowing from the beech forests. Fertilizer from decomposing beech leaves is also an important source of nutrients for local fields. People living at the foot of Mt. Nabekura are profoundly connected to the mountain's beech forests.

About 20 million years ago, a Fossa Magna (geological rift in the ocean) formed across central Japan, eventually developing into a mountain range. It's said that people have lived in the plains of Iiyama for about 20,000 years, and Mt. Nabekura has been covered in beech trees for 10,000 years, since the end of the ice age. With ancient geological features, an immense geologic history, and the influence of heavy snow, Iiyama is home to an incredible diversity of flora and fauna.

Until the 1950s, beech trees were found throughout Japan, and were particularly common in regions of heavy snowfall along the Sea of Japan. However, in post-WWII Japan beeches were considered useless, the soft and easily warped wood making the trees unsuitable for use as a building material or as timber. As a result, between 1955 and 1960, many beeches were felled and replaced with Japanese cedars. However, because people living at the foot of Mt. Nabekura had long understood the importance of beech forests, particularly in providing a water source, the area avoided widespread deforestation.

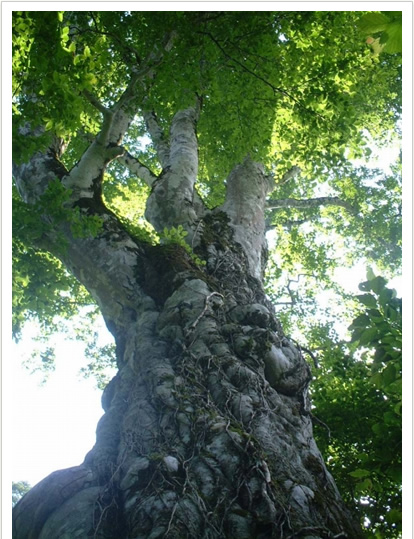

Nevertheless, a plan to fell the beech trees of the Mt. Nabekura state forest was released by the Iiyama forestry office in 1986. Moreover, during the bubble economy era of the late 1980s, the region was focused on maintaining the mountain for ski slopes, including plans for large-scale resort development by various corporations. A contentious dispute errupted between local people who supported the deforestation, and those who favored protecting the beech forests. In 1987, a group opposed to the logging, including a professor at Shinshu University, a reporter from the Shinano Mainichi Newspaper, and the chairman of a local conservation organization, discovered two gigantic beech trees standing quietly in a deep gorge. One was covered in rough bark, rising so high it seemed to touch the heavens. The other was smooth and supple, standing straight and elegant. The group named the trees Moritaro and Morihime. With this discovery, the nature-conservation movement began to gain steam. At the peak of the bubble economy in 1990, newly inaugurated Iiyama mayor Kunitake Koyama scrapped the plans for deforestation and resort development, citing the need to protect the beautiful beech forests so loved by locals, and anxiety over large-scale resort management. This was recognized as the local nature-conservation movement's first victory in Japan. The Japanese bubble economy collapsed just after this dispute, and as a result, Mt. Nabekura's beautiful beech forests have been conserved until the present day.

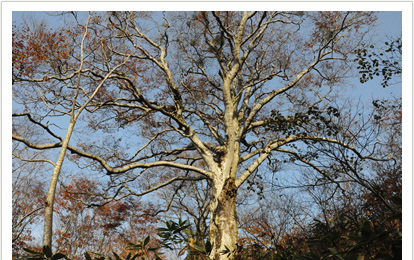

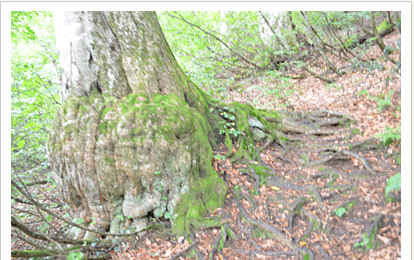

After Moritaro and Morihime, various other gigantic beech trees were discovered, including Kenshin Buna (named after a Nagano warlord from Japan's Warring States period) and Kobu Buna, named for the prominent lump on its trunk.. These ancient beeches were clustered in an area that came to be known as "the valley of gigantic trees," which attracted many hikers. While many beech forests are difficult to reach, Mt. Nabekura's close proximity to settled areas make it possible for anyone to experience the mountain's untouched beeches. This is one of the primary reasons that the number of visitors to the mountain has increased.

As visitors to the mountain increased, Kenshin Buna collapsed in 1989, and Kobu buna toppled in spring 1999. Morihime, the most easily accessible tree, also began shedding leaves out of season, and suffered from woodpecker holes and withering branches. In response to concerns that the ancient beech trees would all eventually collapse, the Iiyama Beech Forest Club was founded in 2000 to promote Mt. Nabekura conservation efforts. These initiatives included treating weakened trees with the help of arborists, trail maintenance, clearing fallen trees, and building retaining walls. The organization also facilitated discussions on the use and preservation of natural resources, and attempted to unify the approaches of all people concerned.

To preserve the beautiful forest for the next 100 years, the Iiyama Beech Forest Club is managing and protecting Mt. Nabekura's beech forests now.

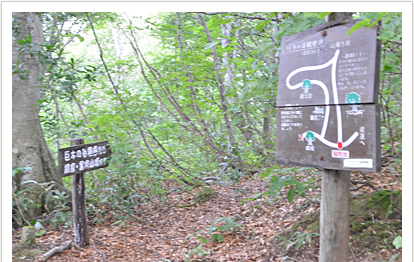

The mountain trail to Moritaro, which stands calmly in the Valley of Gigantic Trees, includes non-maintained sections designed to maintain the primitive state of the forest. These areas may be difficult to traverse, so please go with a guide if possible. The mountain trail entrance is about 2 kilometers from the Tamogi-ike pond. To prevent large numbers of people from hiking up the mountain in non-trail areas, there is no information posted on nearby highways. A board with directions is posted just before the thickly wooded trail entrance, and hikers can walk through various types of trees. A marsh area runs to the right of the mountain trail, and hikers can see the remains of charcoal-grill kettles left behind by former residents.

For a while looking only thin and low beech trees, but a view suddenly opens, and gigantic beech trees of 100-200 years old come to appear. Here is a boundary between the private forest and the national forest, it is obvious that gigantic trees remain at the side of the national forest. There are brown beechnuts on the tip of many branches. There seems to be a true good harvest year at 6-8 cycles of year and apparently this year is a good one. Beechnut has a fragrance, sweetness like cashew nuts and is an important food source of wild animals.

After about 15 minutes, the road curves 90 degrees to the left and a giant beech comes into view, bowed deeply by the weight of fallen snow. With roots grown long and thick, the tree seems to tell of Mt. Nabekura's severe natural environment. Stepping over shallowly buried roots, it's another 15 minute walk to the crossroads, where divergent trails lead to Moritaro and Morihime. This crossroads is about 1.2 kilometers from the entrance to the mountain path.

Beech leaves are one of the tree's special features. While the leaves of most trees have veins that bulge at the tip, the veins of beach trees narrow slightly. These leaves allow beech trees to store more water than most other trees. This special feature is easy to see in fallen leaves. Leaves from the Japanese oak, as well as many other trees, have a saw-like edge, and veins that run toward this jagged edge. In contrast, beech tree leaves are oval shaped, tapering to a point, and the veins run towards the wavy, indented edge.

The withered figure of Morihime stands 200 meters from the crossroads. Confirmed to be dying in summer 2011, the tree has now lost all of its leaves. A 5 meter rope is stretched across this side of the trail, preventing hikers from approaching too closely, although in the past many visitors sat beneath the tree for meals. The pressure of thousands of feet is said to be one reason for Morihime's withering. Because beech trees are rooted shallowly to absorb water and nutrients, they are weak and easily damaged by the weight of climbers. As a result, the life spans of these beeches are often shortened.

Today, the rope serves both to protect climbers from Morihime's collapse, and to allow vegetation in the area to return to its natural state. The vegetation has largely re-grown, and the old tree's collapse has allowed sunlight into the valley, promoting the growth of young trees. In this way, the forest's natural cycle continues, allowing a new generation of gigantic beech trees to grow in the future.

Growing straight and supple, the tree was named Morihime (forest princess) for its elegance. However, a survey confirmed its death in July 2011. The beech is said to be between 300 and 400 years old.

Easily reachable and close to the trail, Morihime's withering can be traced to pressure from countless hikers treading on the roots.

A ten minute walk past the crossroads, Moritaro stands calmly in the middle of the forest. With an overwhelming sense of presence, the tree is estimated to be more than 400 years old. In 2004, it was designated by the Forestry Agency one of the "100 giants in the forest," a selection of gigantic trees in Japanese national forests. Like Morihime, Moritaro's roots have also been exposed by tread pressure, so the tree is currently roped off for protection.

The beech trees lifespan is thought to be about 400 years, so Moritaro will likely not live much longer. Moritaro will return to the soil in the near future, and new trees will begin the struggle for existence. Walking through the valley of the gigantic trees, visitors can experience a sense of eternity and natural divinity, and feel firsthand the connection between human beings and the beech forest-provided water.

Selected as one of the "100 gigantic trees in Japan," the over 400-year-old Moritaro stands calmly in "the valley of gigantic trees."

After examining the tree, an arborist estimated Moritaro's vitality at a 4 (out of 5, with larger numbers indicating a weaker tree). Morihime is currently at level 5. However, in 2011, brown nuts still appeared on the tips of the beech, a testament to Moritaro's endurance.

Mr. Hoshino was born in Fukushima Prefecture in 1968. After experience in film production, he began to work free-lance in 1999, specializing in mountain and outdoor magazine work. Traveling on foot from the Sea of Japan to the Pacific Ocean, Mr. Hoshino also experienced high-altitude climbing in the Himalayas. Afterwards, he became enchanted with American backpacking, traveling repeatedly to Sierra Nevada in California, as well as climbs in Alaska and Canada.

In addition, the Northern Japanese Alps, Tsurugidake, Tateyama, and the Kurobe River headwaters have served as a main source for his photos and articles. On the other hand, Mr. Hoshino frequently goes to Mt. Yabu in northern Nagano prefecture, photographing people, animals, and the remnants of mountain village culture.

His work has been published in “The Alpine Guide 8: Tsurugi/Tateyama Mountains” (Yama-kei Publishers Co.)

Mt. Nabekura is a forest mountain. Trees gathered one by one, eventually becoming a forest, and forming a mountain. So I see Mt. Nabekura less as a mountain than as a forest. Whenever I go there, I say "I'm heading to the woods!"

I've been going to this forest for nearly 10 years, and my favorite thing about it is the small size. Compared with the untouched beech tree forests of Tohoku Shirakami, Mt. Nabekura is tiny, which suits me. The mountain and forest are just the right size for a "hometown" mountain, and allows a feeling of closeness, despite the number of trees. Still, the tiny forest conveys a sense of depth, seeming to continue endlessly. I always end up wanting to back, which is after all, probably the reason I keep on returning.

As a broad leaf forest with beech trees at the center, the seasonal changes are spectacular. There are high points to each season, but my personal favorite is winter, especially snowstorms. On snowy days, I feel that I can really connect with the forest, and I think these conditions bring out the true spontaneity of nature.

Travel Agent Registration No.2-492 certified by Governor of Nagano Prefecture ANTA PARTNER

Copyright © 2024 Shinshu-Iiyama Tourism Bureau All Rights Reserved.